What, Me Gone ?

What, Me Gone ?

By John Robert Tebbel

William M. Gaines went to bed Tuesday night, the Second of June, 1992, and never got up again. He founded Mad Magazine and so belongs to that small company of Americans, along with Hefner and Steinhem and Felker and Glaser, who, after World War II and in the face of King Broadcasting, made magazines that changed our lives and our thoughts and our culture.

Mad is our national humor magazine, by default, as befits comedy. We outgrow it, but we never forget it. Gaines never put out more than eight issues a year and he never broke a sweat.

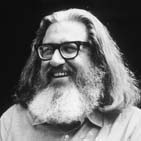

But if Gaines's life finally was comedy, the first act was tragedy. The image of Gaines we know today is the Falstaff who smiled out from countless profiles and light features. It became as familiar and predictable as, some criticized, his magazine. But Gaines the mad publisher, the crazy guy with the zeppelin model in his office, was a man who forty years ago re-invented the comic book, and was brought to earth by his competitors for his trouble.

In 1947, his father's accidental death put Gaines, late of the U.S. Army and New York University, unexpectedly in charge of the family comic book business, the first of his generation ever to run a comic book company. After a shaky start (he'd not been groomed for the job, and his father openly dressed him down at the office) Gaines took an interest in the business that grew into a creative obsession. By 1950, he hit his stride and, with editors Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman, created the latest and the greatest of the under-the-covers-with-a-flashlight genre. Tales from the Crypt, Weird Science, Shock Suspensestories, Frontline Combat, and a few other titles made the struggling company profitable and Gaines a fully employed pop culture mentor of the first magnitude.

But this upstart Jewish kid was soon put out of business by a crusading psychiatrist from the old country, a nasty bunch of Senators, and a coalition of PTA and American Legion, sheriffs and bishops, editors and aldermen. The Comics Code that was created to deflect the heat couldn't help Gaines. The slander was so thorough that his books were returned unopened by retailers even after the Code seal was applied. By the end of 1954, after just a four year run, the EC comics were all gone, except for the satirical Mad, reborn as a magazine beholden to no advertisers. Mad was built on the bedrock of the EC Comics talent pool, a one-office golden age that changed comics for a while and the landscape of our imagination forever.

Once bitten, twice shy, Gaines was re-invented in the public consciousness as the fat and jolly one-trick pony of the publishing business. The smiling, bewhiskered face beamed from dozens of admiring profiles in newspapers and magazines, some of which were the same ones who earlier joined the lynch mob, or stood by while the media ate its young. The more sophisticated subversion he was perpetrating with Mad's relentless satire of mass culture went unnoticed by the culture guardians who cleaned up the comics. Mad and Gaines were quite tolerable to our society and went on their merry way.

Like Walt Disney's, Gaines's paternalistic management style didn't suit everyone. But those who found it compatible were rewarded with long careers and a seldom felt atmosphere of warmth and candor. Bruce Springsteen has said that the secret to rock and roll is the band itself: assembling it, keeping it together, making the art form fit the artists who are making it. And Gaines figured out how to keep the band together. Many Mad creators from the beginning of the magazine as a comic about comics are still working. This is the source of some of the complaints, that there's too much from the same old guys. While acknowledging this, I'd be first in line to buy a magazine put together by eighty per cent of the people who made the first five years of National Lampoon.

Bill Gaines's memorial service on Friday, June Fifth, overflowed the auditorium of the Time & Life building in New York City's Rockefeller Center.

Lyle Stuart (1)

Lyle Stuart (1)Bill never played anybody's game. Bill created his own world, created his own rules. And to quote an editorial in today's New York Times that described him as having an "adolescent irreverence for pompous personages and sacred institutions."

For example, you may be amused to know that Bill selected this hall (2) for his memorial. He was here one day with Annie and he turned to Annie and said, "Listen, when I die, I'd like my memorial to be here." And that's where it is.

I first met Bill (3) when we were nine years old, but I didn't talk to him. He was a kid standing in the schoolyard of P.S. 178 in Brooklyn, on King's Highway. And he was pointed out to me as the son of a man who was publishing a comic book. (As you know, his father invented a form of the comic book. (4)) And I walked over and stared at him because I didn't know anybody who's father had anything, never mind a comic book. This was in the depression in about 1933. And I remember that Bill had a big button on because the New York Evening Journal was conducting a contest and you'd have a comic character with a number and each day they'd print numbers and if it was your number you'd win some money. I didn't see him again for maybe fifteen years, although he went to my high school. We didn't know each other.

From time to time I'm going to intersperse this with remembrances of my own. But in terms of Bill not playing the game, I'd like to introduce as the first speaker the corporate part of Mad magazine, Mr. Bill Sarnoff.

Bill Sarnoff (5)

A couple of incidents kind of show the type of fellow he was and that we knew and loved.

The first was back in about 1975, a little earlier than that, when Warner Communications took over the big building in Rockefeller Plaza and a lot of the divisions were moving into the building. And I went over and I asked Bill, I said, "How would you like to move Mad magazine with the rest of the company?"

And he said, "Well, if you were a grown child, would you like to live with your parent?"

[audience laughs]

They stayed on Madison Avenue.

The other one that was kinda fun for me, again, this is a little later in the seventies. Warner has-had and has-a unique management philosophy, wherein the executives are rewarded enormously well when they perform enormously well. And I went to Bill and I said, "Gee, uh, Bill, I'd like to work out some sort of profit sharing arrangement with you. Not taking anything away. Whatever you're getting you're getting. But this is just added to it. We'd like to introduce something where you have a possibility, as Mad does better, that you'll be rewarded even more meaningfully."

And he said to me, "Bill, I'm really not interested."

[small laughs]

I said, "Really, Bill, there's no hidden agenda here."

[big laughs]

"This is only-this can only be good for you. Please believe me, only be good."

And he said, "Bill, I'm really not interested."

And I said, "Well, okay. You know, if it doesn't make sense to you. But, could you tell me why?"

And he said, "Sure. Because that philosophy assumes that I'm not doing everything I can to make Mad as good as it can be. And I tell you that's never been the case, and it never will be the case. So if you think that by giving me a profit incentive I'm gonna work harder, you're absolutely wrong and you've got the wrong guy here."

And that's the kind of guy Bill was.

Stuart

The next time I ran into Bill I received-well let me tell you I was writing comic book continuities for Billy the Kid and John Wayne comics. And one day I went to a newsstand and saw this strange looking comic, and it turned out to be Number Four of Mad. And I bought it and was very impressed. And back issues were twenty-five cents each so I sent a check for seventy-five cents to Bill. Well, it turned out that Bill had been reading a monthly iconoclastic tabloid that I was publishing called, then called Expose later called the Independent, and had been lying awake at night dreaming of meeting me. [He laughs] OK? So he sent back the seventy-five cents, together with a big stack of his comics, showing how, inspired by my paper, he had one story in every comic against racism. Whether it was against black racism or Indian racism, or Cath-they were marvelously inspiring and very educational for children.

So we eventually met. And I was struggling. And Bill became the first stockholder in the Expose/Independent. And he said he would put five hundred dollars into it. But he explained that he collected money in lots of five thousand, and so he had to get the five thousand that he was saving then. And, after that, he would put five hundred in.

[laughs]

I thought this was a little strange, but, eventually, he put the five hundred in. Expecting, I suppose, that he thought it was a contribution, and over the years, he got back the five hundred and a couple of thousand more. And so that wasn't a bad investment. He made one other investment which started my publishing company, but I'll tell you that later.

One day he called me and asked me if I could come down to his office immediately. And I came down to his office, which was then at 225 Lafayette Street, and he asked me if I wanted to be his business manager. Well, I'm a high school dropout. I don't even know-[he laughs] And I said, "Sure."

[laughs]

And he said all I had to do was move my office into his building and work four hours during any twenty-four-hour period, five days a week. And I agreed. And thus I became his business manager. And I was signing checks. And he told me to make out a salary check for whatever I wanted. Well, the previous business manager had been making three hundred and fifty dollars a week. For about a year I took seventy-five dollars a week, like a jerk. And he was very amused at the whole thing.

One day we published a sister book to Mad called Panic. And the police came down to arrest Bill. And Bill was very nervous about the whole thing and sat in his chair, shaking. And I went in and I said "Listen, if they arrest you, you're gonna be dead." And that would've been forty years ago, by the way. So I said, "Let 'em take me."

So the police called and they said, "Yes, they can take any executive."

[laughs]

So I went down to the Elizabeth Street station, where they had a few hours before booked Frank Costello. And I felt very important. And when the case came to court, Bill was absolutely petrified. He felt so guilty. Someone came to him and said, "You can bribe the judge for ten thousand dollars." And he thought about that. He wanted to do anything that he could do to save me. And I knew that the case didn't have any basis at all. And sure enough, the judge was angry as hell and threw it out and reprimanded the police for even bringing, you know, a ridiculous case like that.

Three months later, Walter Winchell, with whom I was feuding, and whose television career I eventually ended, carried an item in his column stating any newsstand or book shop selling the filth of Lyle Stuart will be subject to the same arrest. And I sued Winchell and that was the first libel money I ever collected. And that started my publishing house.

[laughs]

So Bill and I, in one way or another, have done a lot for each other.

I'd like to introduce now someone who is a key member of Mad and who you've seen on television again and again, Dick DeBartolo.

Dick DeBartolo (6)

Dick DeBartolo (6)I never met Bill Gaines.

[laughs]

But I was walking by and I saw an audience and a microphone and I couldn't resist.

Cathy and Wendy asked me to please keep this sort of lighthearted. And they gave me a story that they would like to relate that they feel that they would break down if they told, an early remembrance of Bill. But first, among my feelings on Bill is that this has been a very sad week because Wednesday we lost Billy. And then, Thursday, I found out I was not in his will.

[laughs]

Thirty years of ass kissing and not even a bottle of wine.

The best practical joke ever was the Mad cruise this past September.

Billy loved the Marx Brothers, loved the scene where all those people went into the cabin on the ship (7).

And one night on the ship one of the officers said, "You know, we're very honored to have the Mad staff aboard. Particularly honored to have Bill Gaines aboard."

And I said "Would you like to play a trick on Bill Gaines?

"Oh, yeah! What do you need?'"

I said, "I need, like, three engineers with, like, big wrenches. I need waiters with serving trays. I need a lot of those maid's carts." And he's writing all this down.

And he said "How many people?" "I said, "Well, the Mad group is forty. I need fifty crew."

"I can do it!"

So we assembled them all on the deck above Bill's cabins. And then we just ran through the halls and just said "Do you know who Bill Gaines is?"

Yes.

"Do you want to play a joke on him?"

Yes.

One couple said, "I have a crying baby."

I said, "Bring the crying baby!"

[laughs]

And Maria [Reidelbach] went in and said "Bill, my TV's broken." You know Bill. Often, Bill's idea of casual was underwear. So, fortunately, Bill was casual in his cabin, and Maria went in and made sure he had something on. And then there was a knock on the door, and Edwin went in and said "Bill, I want to talk to you about the current issue."

And thirty seconds later, someone else went in. And then it just accelerated. And then we got a maid with one of those big industrial vacuum cleaners. I said, "There's a big fat man on the couch. Plug it in. Turn it on. Never shut it off."

And for nine minutes we filled his cabin with a hundred some odd people.

That night he called me. He said, "Dick, thank you, thank you, thank you."

I said, "Billy, can I have a raise?"

He said "No!" and hung up.

[laughs]

My final conversation with Bill, Monday:

"Billy, how you feeling?"

"Dicky, I'm not feeling well."

I said, "Billy, you've not felt well in the past. You've always bounced back. You can bounce back. I know you will."

He said "I know I will, too."

And I said, "But Billy, if you don't, can I have that new thirty-five inch color TV you just bought?"

So my last remembrance of Bill was him laughing. And I love Bill. And I love his family. And I love Annie. And thank you all.

Stuart

Recently there was a marvelous book about Mad written, put together by a woman whom Bill liked, as against the woman who he wouldn't let do the book. And she's here, would like to say something. Her name is Maria Reidelbach.

Maria Reidelbach (8)

Maria Reidelbach (8)I knew Bill for only four years, but in that time I came to know him well. When I began to write the history of Mad, I had every intention of maintaining a professional distance, but I hadn't counted on the steamroller that was Bill's personality. When my mother became ill soon after I'd begun to work and I had to return to my hometown to care for her, Bill called regularly to see how she was and to see how I was. And his calls lifted the spirits of everyone in the house. My reserve developed a crack.

Then I was invited to join the Mad trip (9), this one to Germany and Switzerland. A research goldmine for me; all the Madmen would be in one place. They would be a captive audience. During the trip Bill mostly stayed in his room sitting in his underwear reading mystery novels. It was pretty hard to be professional while chatting with the hulking half-clad man boisterously laughing.

He raved on me about my smoking a lot. He didn't do it because he disliked smoke or because he wanted to feel superior. He did it because he really cared, and it was maddening but his persuasion has helped me try to quit.

He was impossible and he was impossible in many ways. He ate impossible amounts of food. He was impossibly disheveled. His laughter was impossibly loud and long. At first, I thought it couldn't be genuine, but it was.

And Mad, in the middle of the 1950s, when the competition was getting bigger, glossier and more colorful, it was ridiculous to launch a small black and white newsprint magazine that dared-no, it delighted in poking a finger at the American dream. It was suicide not to take advertising. It was impossible. Yet, forty years later, it's hard to name another magazine that's had the impact that Mad's had on American culture.

Bill immensely valued Mad's artists and writers, yet he was stubborn about artist's rights; refusing to bend just a bit. He was just impossible. He cared an inordinate amount for an extraordinary number of us. About our health and our love lives, our joys and our sorrows. How could one man have such love in him? It was really impossible.

It was impossible not to love him back. And now he's gone and it seems impossible.

Stuart

One day Bill and I were riding in his Cadillac and he said, "You know, sometimes when I pass a bus stop I see those people standing there. I think they hate me."

And I said, "Bill, you have to get some self-esteem." And I suggested he see a psychiatrist, which he promptly did.

On [one] occasion, [Bill] was going on vacation, and he had to pay [the psychiatrist] whether he was there or not. Four mornings a week, a hundred dollars an hour, or forty minutes. And it bothered the hell out of him. And finally he went to see [the psychiatrist] and he said, "Listen, I'm gonna be away for the next two weeks. Every morning, from 9 to 9:40 in the morning, I want you to come in here, sit, and think about me."

At a certain point there were some nuts. One was a psychiatrist (10), one was an attorney (11)

and these nuts felt that comic books were what ruined America. This is before Ronald Reagan, before Nixon. So the Senate committee (12) decided they could get a lot of publicity, a lot of mileage out of investigating comic books. Everybody ran for cover and I, who was then Bill's business manager, suggested that he volunteer to be a witness. And he was the only person who volunteered to be a witness to defend comic books. And we stayed up all night and wrote a speech that is now a historic speech. And he delivered it very well. And when he was through, there was some antagonism on the part of the attorney for the committee because inadvertently we had offended him. These were the days when you were either pro-Franco or anti-Franco depending on how you felt about the Catholic Church and so forth. And Bill ended the speech saying "Let's not make this country another Russia or Spain." (13)

And this guy jumped up and said "Are you through?" And Bill was taken aback because he had come as a friendly witness.

At any rate, Senator Kefauver, trying to attack him, kept going through some of the covers and then held up a cover where somebody was holding up a woman by the head. And he said "Mr. Gaines, do you consider this in good taste?" (14)

Because Bill had said all his comics were in good taste, Bill said "Yes, I do."

And the Senator said, "Well, how would it have been in bad taste?"

And Bill, remembering the original art, that he had turned down, said, "Well, if the head were held a little higher, so that blood was running out of the neck."

And from then on in the comic industry, people talked about, like A.D. and B.C., before Bill Gaines said "if the head were held a little higher" or after Bill Gaines said "if the head were held a little higher." And that was the beginning of the end of the comics as we knew them.

I then suggested to Bill that we organize an association to defend comics. And in those days the nicest news any comic publisher could have was that one of his competitors, not that he died, but that he died a very painful death. And Bill said "They'd never come."

And I said, "Let's try."

So, at Bill's expense, we invited them, one by one, to have lunch at Toots Shor's. And finally they all said, "Well, I would come, but nobody else would come."

And finally we had the meeting. And we organized the Comic Magazine Publishers Association. And then we found we couldn't join, because they took the position that they didn't want any violence. They didn't want anything said against American institutions (15). And, after all, Mad was a lampoon comic. So we couldn't join.

And then Bill was looking for a wine and liquor shop to buy. And I suggested that he turn Mad into a magazine. And he kept saying, "But I don't know anything about a magazine."

And I said, "Bill, you can learn." And that was the beginning of Mad as a magazine. And I should have invested some money in that one.

The next speaker is Joe Raiola.

Joe Raiola

Hi. I've been Associate Editor at Mad since 1985.

Bill was an atheist, and I used to talk to him about this because you know it occurred to me that as atheists went Bill was a very religious atheist. I remember one day I went to his office [and] said, "You know, you are a religious atheist. Because you don't believe passionately. You don't believe as much as people who do believe, believe. And you look kind of like a guru, kind of like a perverted or deranged Zen master. I think you're a religious person after all. I don't believe this atheism bit."

And he said, "Please, will you please get the hell out of here."

But there was one story that really best typified my relationship with Bill. Like I said, we disagreed on everything. I'm skinny, he's fat. He's hairy and I'm bald. And I'm a healthy guy. I'm into nutrition and vitamins and vegetables and bean sprouts. And Bill would eat anything that moved. I mean this is a guy who ordered steak by mail and got cases of frozen beef in his apartment. So one day Bill calls me into his office. He says, "I want you to go downstairs to the corner of 53rd Street and Madison. It's gotta be 53rd and Madison. It's gotta be the southwest corner. There's a hotdog vendor on that corner. I want you to get me two hotdogs with mustard, sauerkraut."

I said, "Bill, I can't do that." I said, "Bill, not only can't I do it, but you don't want me to do it."

He said, "Why don't I want you to it? I'm hungry."

I said, "Because you know I'm a vegetarian. You know it would be against everything I stand for. It would be against my principles. I am a man of integrity, Bill, like you are. To go down and buy you hotdogs and bring them to you... you would have no respect for me. So you don't want me to buy you these hotdogs."

And Bill said, "Wrong!" He said, "Not only do I want you to buy me these hotdogs, but Joe, you are the only person in the office I could trust to bring the hotdogs back without eating them."

[laughs]

You see, his logic was twisted. But it was irrefutable. So I felt defeated. And I trudged down to the hotdog stand. And I get the two hotdogs and, you know, the whole deal. And I bring it back to him.

And he said, "Don't go anywhere. I'm not done. I want you to go into the refrigerator. And I want you to get me a diet orange soda."

Now this guy bought diet orange soda by the case. He had cases of diet soda and he had frozen cups in the freezer that he'd fill half with water so they'd freeze up and people would pour his orange soda into a frozen cup and bring him the diet soda.

And I said, "Bill, I draw the line at the diet soda, man. I brought you the hotdogs but I'm not bringing you the diet orange soda because I happened to read in today's New York Times,"-and this is true-"...that diet orange soda is the worst thing for you. Man, it's got chemicals and additives. They put shit in it you wouldn't believe, man. You can't have it. You can't have it. [And] something else I read about it. I read it's the worst thing for your gall bladder. It eats away at your gall bladder."

Bill looks at me. He says, "Fuck you! They took out my gall bladder in 1963!"

[laughs]

So he'll be missed. He was a rapscallion. And he was so profoundly deranged and lovable.

Thanks for this chance to talk.

Stuart

A couple of years ago, my wife Carole and myself and Annie and Bill were out in California, where Bill was awarded, on national television, an award by the Horror Hall of Fame. And there were a lot of directors and producers, some of the biggest directors and producers of our time were there. And I was amazed as one after the other came over to Bill and told him how much Mad had meant to them as children. One of them said, "You taught me to read. I never wanted to read till Mad came out and then I learned to read."

And the influence of Bill Gaines isn't limited to the people in this room or the people in this city. It literally went around the world. Mad affected the way millions and millions of people think. It gave people a dose of skepticism, a dose of irreligion, a dose of iconoclasm. I trust that whoever the corporate people are at Time-Life, they'll have enough good sense to keep that team together, because there's a magic that Bill instilled in that organization. And I think the same people can continue to carry on the magic.

I'd like to bring up one of the magicians, Nick Meglin.

Nick Meglin (16)

Nick Meglin (16)Bill Gaines had a logic unique unto himself. For instance, he could stop everyone from their work at any time, to try to hunt down the culprit who made a dollar twenty-seven personal phone call to Des Moines without recording it.

When John Ficarra (17) made him aware that the time devoted to this investigation-the actual cost per hour for eight of us to search through our address books, calendars, appointment books-could cover the cost of a three hour call to Tibet, he just snarled and said, "I had to assemble you here anyway to talk about our trip. This year I'm taking you all to Switzerland and Paris." And so, thirty artists, editors and writers trekked through the wonders of Europe, all on the dollar twenty-seven we saved tracking down a phone call to Des Moines.

I had my first insights into Bill's uniqueness on the very first Mad trip. We were staying at this plush hotel in Haiti, owned and operated by one of Bill's friends. It was the first morning we were there. Since I'm an early riser, I quietly went out to the pool for a swim. No one's up yet. I get to the pool, and there, in the deepest part, a breakfast table, chairs are set up, dishes, all on the bottom of this pool. Well, God, what did those maniacs do last night? Bill is going to be livid. So, all alone, piece by piece, I dragged every piece out. By the time I'm finished, I'm sitting by the pool, the hotel staff is setting it up, having some coffee, and all of a sudden the world class eaters come out. These guys arrive for the early sitting so that they can also make the second sitting. Bill gets to the pool. He looks in the water, says, "Goddamn it, someone emptied this pool. It took us an hour and a half to do that." Never knew it was me until Lyle Stuart published Frank Jacobs's book, The Mad World of William M. Gaines (18) and Bill, when he found out, never forgot that.

Well, Bill Gaines was a big man, and to those of us that knew him, worked with him, lived with him, to those of us fortunate enough to call him boss, friend, husband, we know it takes a big man to house a heart as big as his was.

Stuart

I spoke earlier about the influence he had, and I just thought of one incident. Bill and I both, as I said, went to James Madison High School in Brooklyn. And Madison turned out a lot of celebrities, Irwin Shaw, Garson Kanin, probably forty people whose names many of you may have heard of. One year I heard that Bill was gonna be the guest speaker at the graduation. And I called him about it and he invited me to come along. He knew I had a car and I'd drive him there. So I drove Bill and Ann. The graduation was at Brooklyn College. Now when I went to Madison the school was largely middle-class Jewish. It was an upscale kind of community. Now, it had changed and it was about eighty per cent black and ten per cent Hispanic. And I sat in the auditorium at Brooklyn College as the graduates marched in, hundreds and hundreds of them, mostly black. And I thought, "Boy, have they picked the wrong speaker." And then the dean got up and said today our guest speaker will be William M. Gaines and the crowd went wild. They screamed up and down. I think they couldn't quiet them, they were so happy, so jubilant. His influence reached everywhere.

About five and a half years ago, I got a letter from Bill. I'd been pushing him to go to Pritikin Longevity Center for his health. Carole and I went out there several times. Didn't do me much good; it's done her a lotta good. And he wrote to me and he said, "What if I gave you a choice." Because I was also pressuring him to marry Annie; they seemed to get along so well together. "What if I gave you a choice: either marry Annie, or go to Pritikin."

And I thought, "That was a tough one." It gave me a difficult weekend. And finally I said, "Listen, go to Pritikin, because if you go to Pritikin you're going to stay healthy. And then you'll be able to marry Annie."

And he wrote back and he said, "I just said 'What if I gave you a choice.' I didn't give you the choice."

[laughs]

And a couple months later we got a letter inviting us to a party at Windows on the World and it said, "Please be there at 7:15 because at that time Annie and I are getting married." And that was the wedding invitation. And it was quite a party.

I think that since there are a lotta people standing we're not going to extend this too much longer. But I don't have to tell you all that many people could stand up and talk about how much they loved Bill. I don't know anybody who is so much loved by people. Everybody loved him. He was so warm and generous and caring, as you've heard from the people here.

The world is certainly a poorer and colder place without him. But I just want to read something quick. I publish a private publishing newsletter called Hot News. And this report appeared in my March issue about a party. It was a fifth wedding anniversary party for Bill and Anne Gaines. Bill decided he was going to do a repeat of his wedding. The same place: the ballroom at Windows on the World. The same entertainer: Henny Youngman. There was a live orchestra and lots of food, drink, and fun. And Carole and I sat next to Bill. And Bill turned to me and said, "You know, the food was lousy five years ago and it's lousy today."

[laughs]

And then he made a brief speech that was both funny and touching. He spoke of the people present, including Walter Kast who he described as quote, "The friend I've had the longest. He's about sixty-eight this year. I've known him since he was two, when I fed him a pearl necklace pearl by pearl," unquote. Present also was an Army buddy Bill hadn't seen in forty-five years. His name is Ed Ginger, and he recognized Bill on a TV show and got in touch. But we were puzzled, because Carole and I sat next to Bill and he wouldn't identify a mystery guest who sat on his other side. Finally, in his speech, Bill revealed that the fellow's name was Leo Veer. "Believe it or not," said Bill, "if it hadn't been for Leo, Annie and I wouldn't have been married. I would never have had the nerve to ask her out. Leo is Annie's former boyfriend, who walked into my office with her twenty years ago. I took one look at Leo and realized that if Annie could be interested in one fat man she could be interested in another. She was a chubby chaser!"

[laughs]

When the hundred and sixty guests stopped laughing, Bill continued. "Annie, of course, is the best thing that ever happened to me. She's the dearest, most wonderful wife and has made the last twenty years the best years of my life. I love her so very much and consider myself blessed to have ever had the good fortune to win her affection. I love her almost more than life and almost more than food."

I know that all of you who loved Bill will do everything possible to support Annie and Bill's children in their grief. And I hope you'll never forget that she was the most precious thing in the world to Bill and that what you do for her you do for Bill.

Goodbye, dear friend.